Hemophilia drug interferes with APTT-based assays

“So even though emicizumab is expensive—about $430,000 per year—it still may be cost-effective in certain populations,” Dr. Adcock says. The report makes the case that third-party payers should cover emicizumab because, over time, it will reduce treatment costs. But the ICER report also warns that some controls on the price may be needed: “Given that emicizumab may gain indications for broader use, indication-specific pricing will likely be essential to tailor the price to reflect the clinical and economic value of the drug in different patient populations.”

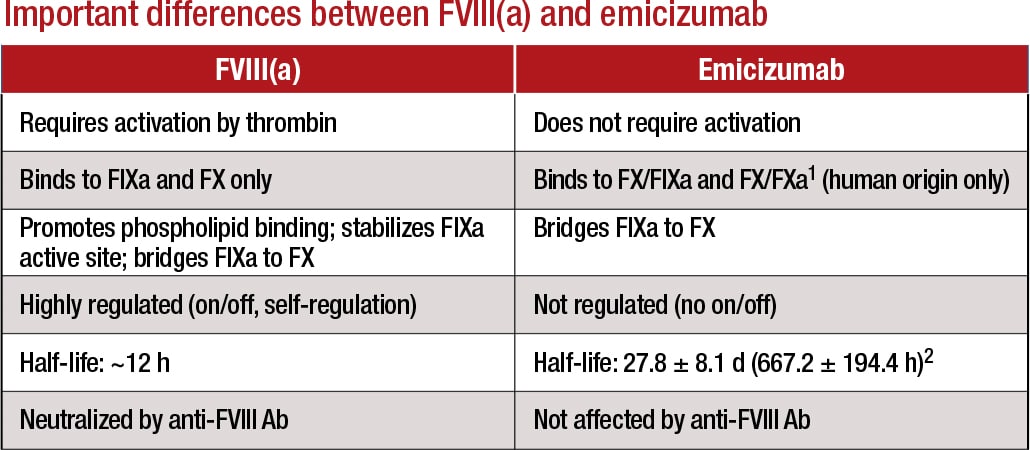

Emicizumab works by replacing or mimicking the function of the missing cofactor, activated factor VIII, says Stefan Tiefenbacher, PhD, vice president of LabCorp and technical director of Colorado Coagulation, a member of the LabCorp Specialty Testing Group. “Emicizumab bridges factor IXa and factor X, bringing them into proper alignment—which is normally the function of activated factor VIII. However, there is a big difference between factor VIII and this bivalent antibody: Unlike factor VIII, which is highly regulated, emicizumab, once administered, does not require activation and circulates in the patient in its active form until it is cleared from circulation.”

Dr. Tiefenbacher

At the 2018 Scientific and Standardization Committee meeting of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Dr. Tiefenbacher, who develops drug-specific assays for clinical trials, presented a special session on practical considerations, including laboratory issues, that emicizumab raises.

This bispecific antibody has a long half-life of 28 days, he explains. “With more conventional hemophilia factor VIII replacement treatments, the ‘wash-out’ period of the factor product is usually a few days, maybe a week for the newer extended half-life products. Thus, you can safely perform a factor VIII inhibitor assay after a few days of wash-out without having to be concerned about the factor VIII replacement product interfering in the assay.” If, on the other hand, a hemophilia A patient is treated with emicizumab, the bivalent antibody circulates in the patient’s blood for up to six months after the last treatment, creating significant challenges in the laboratory when APTT-based factor activity and inhibitor are ordered, he says.

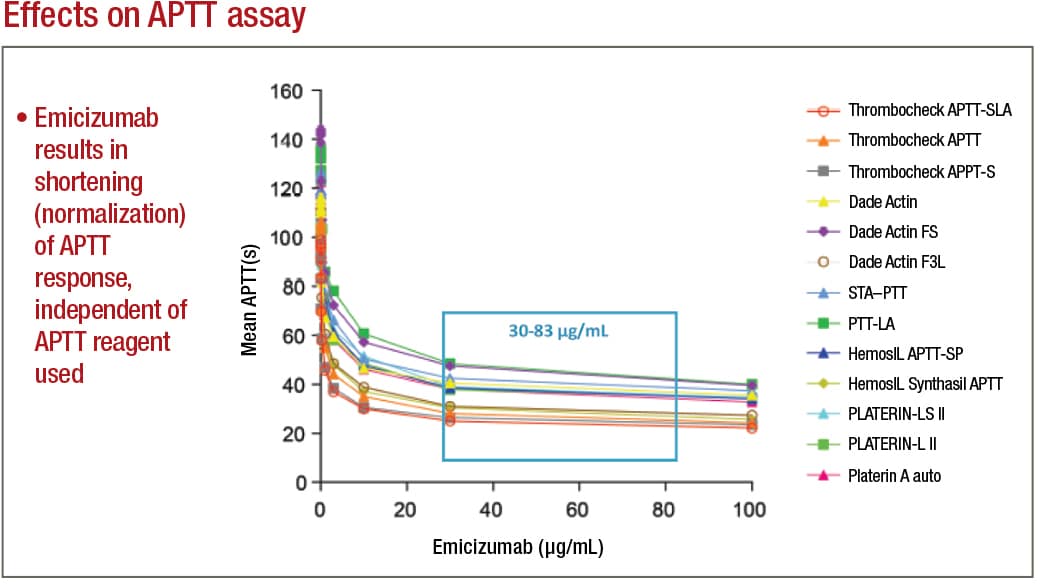

In APTT-based assays, emicizumab will result in a shortening, or normalization, of the APTT response, which in the one-stage factor VIII activity assay will lead to an artificial overestimation of the factor VIII activity level, as high as 500 percent or more. Emicizumab, even if present at very low concentrations, can thus give the appearance that a particular patient has either normal or even elevated circulating levels of factor VIII, Dr. Tiefenbacher says.

If laboratory professionals aren’t being educated and aren’t aware of these APTT-based assay interferences, he adds, they are at risk to report incorrect laboratory results, which could adversely affect patient care. For example, if the inhibitor level in a patient treated with emicizumab is monitored and reported using a standard APTT-based inhibitor assay, the assay will provide a false-negative result, which the treating physician could incorrectly interpret as the patient no longer having a measurable FVIII inhibitor titer, he says.

Genentech wanted to forestall this kind of false-negative by making an alternative assay available: the chromogenic two-stage inhibitor assay. “As far as chromogenic assays go,” he says, “there are currently five different reagents available in the U.S. Only two or three of these assays utilize bovine-based factor IX and factor X and have been demonstrated to be suitable for the measurement of factor VIII inhibitors in the presence of emicizumab. Should a laboratory use a chromogenic assay that utilizes human-based reagents, it also will be interfered with by emicizumab. Due to the specific design of the humanized bivalent antibody, it does not cross-react with bovine origin reagents, as the antibody was selected to be specific to human factor IX and X.”

When LabCorp receives hemophilia A patient samples for testing, the typical test order received is for a factor VIII activity and a factor VIII inhibitor. Dr. Tiefenbacher provides an example of how test results can go awry: “We had a patient who previously demonstrated with significantly elevated APTTs, factor VIII one-stage activities at around one percent or below, and with an increasing factor VIII inhibitor titer as high as 200 BU. Suddenly, a month later, this same patient presents with a normal APTT result—in fact, slightly below normal—and a corresponding factor VIII one-stage activity result of greater than 500 percent.

Adamkewicz, et al. Poster presentation at Hemostasis & Thrombosis Research Society, Scottsdale, Ariz., 2017; Courtesy of Genentech, Chugai, and LabCorp

“When the medical technologists brought these results to our attention, we suspected that the patient was switched from one of the traditional factor VIII replacement therapies to emicizumab. However, the treating physician appeared to have ordered the standard coagulation assays that are customary for patients receiving traditional factor VIII replacement therapy,” Dr. Tiefenbacher says. This same patient, when tested using a bovine reagent-based chromogenic assay, had nonmeasurable factor VIII activity. “We have since received several other patient samples from a variety of different hemophilia centers where the treating physician continued to order the standard lab testing associated with traditional factor VIII replacement therapy. Thus, there clearly is a need for additional education, both at the level of the ordering physician as well as at the laboratory level where the testing is performed,” he says.

Another potential future challenge for laboratories is that emicizumab is marketed as not requiring laboratory monitoring, he says. “However, one can come up with scenarios where laboratory measurement of emicizumab may be required, for example, when a patient requires surgery in an emergency-type setting. The treating clinician or surgeon and the laboratory will have to know that the patient is or has within the past six months been on emicizumab and that conventional APTT-based screening assays will provide inaccurate results.” It is Dr. Tiefenbacher’s understanding that some institutions are providing patients with bracelets that indicate the patient is on emicizumab therapy and that APTT-based assays cannot be used for monitoring, as is also stated on the drug label.

Since Colorado Coagulation is a reference laboratory, “we don’t always know what drugs the patient is taking,” Dr. Adcock says, “and the technologists in the lab have to exercise good judgment. When we see factor VIII activity that is extraordinary—for example, over 400 percent, where normal is up to 150 percent—then we question if the patient is on emicizumab, and we may reach out to the doctor or perform a chromogenic factor VIII activity assay.” As she explains, “If you want to obtain a semi-accurate activity of the emicizumab, you use the chromogenic human assay. To monitor factor VIII antibodies in patients on emicizumab, you use the bovine chromogenic factor VIII Bethesda inhibitor assay.”

1Lenting, et al. Blood. 2017;130(23):2463–2468; 2Hemlibra FDA Prescribing Information, 11/2017 Courtesy of LabCorp

Dr. Tiefenbacher agrees: “We are a special coagulation lab, so we probably are more experienced in those areas, but it can take some detective work to determine if the observed interference in the patient sample on hand is due to emicizumab or some other type of drug or interference. Oftentimes we have little information provided for a particular sample other than the test order. This is where education and training of the involved parties becomes important.”

It’s also important to note, he says, that “until some type of neutralizer for emicizumab is developed, assay interference—at least in the APTT-based coagulation assays—should be anticipated for up to six months posttreatment. People need to be aware of this and use a bovine-based chromogenic assay when trying to measure inhibitors in these patients.”

Dr. Tiefenbacher makes five recommendations for coagulation laboratories addressing the testing needs of emicizumab patients: 1) avoid APTT-based coagulation assays such as APTT-based one-stage factor activity and factor VIII Bethesda inhibitor assays; 2) where possible, replace APTT-based assays with chromogenic or immunoassay-based coagulation tests; 3) use the chromogenic (bovine factor IXa and factor X) factor VIII Bethesda assay when measuring factor VIII inhibitors; 4) to measure emicizumab, use a chromogenic (human factor IXa and factor X) or dilute one-stage assay with emicizumab calibrator and controls; and 5) work closely with physician customers to provide education and training on emicizumab interference and the selection of the most appropriate tests.

Education will be crucial to avoiding serious adverse outcomes when laboratories test hemophilia patients, says Dr. Young, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “The company that’s marketing the drug is working on educating the community. They are doing webinars and podcasts, conducting symposia at national meetings, and putting out flyers. But one problem will be, if patients are on the drug and somebody just decides, ‘I need a factor VIII level,’ without being aware of laboratory interference, they will misread the results and may make incorrect clinical decisions based on a test that should not have been done in the first place.”Tagged with: Blood/coagulation/hematology (see also Phlebotomy) -- Drug treatments/trials/dosing -- Hemophilia -- Pharmaceuticals --

Related Posts

In hemostasis, two hot-button testing issues

December 2017—Having validation data to support the use of age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs with the D-dimer assay your laboratory uses is a must, and know well the limitations of point-of-care prothrombin time/INR testing. That advice and more was shared in a “Hot Topics in Hemostasis” session at CAP17, presented by Russell Higgins, MD, and Karen Moser, MD.